Radical clock

In chemistry, a radical clock is a chemical compound that assists in the indirect methodology to determine the kinetics of a free-radical reaction. The radical-clock compound itself reacts at a known rate, which provides a calibration for determining the rate of another reaction.

Contents |

Introduction

Many reactions in organic mechanisms involve intermediates that have a key role in the reaction. Understanding these intermediates and their chemical kinetics may be helpful in the predicting the outcome of the reaction prior to performing the reaction itself.[1] Among the different types of reactive intermediates that are involved in synthetic organic mechanisms such as carbocations, carbanions, and carbenes, interests in radical intermediates reactions have increased. A great deal of attention was drawn to them due to the discovery of their linkage in enzymatic pathways and in sonodynamic therapy in the treatment of cancer.[2]

Many techniques have been developed to measure the rates of radical reactions. The two possible ways to measure the reaction rates are direct and indirect approaches. Direct approaches such as the rotating sector method have restrictions that hinder their expansion or application to the wide variety of types of radical reactions of chemical interest.[3][4] In addition, direct methods such as flash photolysis and pulse radiolysis require a relatively large amount of time and expensive equipment. With an indirect approach, one can still obtain relative or absolute rate constants without the need for instruments or equipment beyond those normally needed for the reaction being studied.[5]

Theory and technique

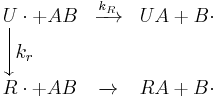

Radical clock reactions involve a competition between a unimolecular radical reaction with a known rate constant and a bimolecular radical reaction with an unknown rate constant to produce unrearranged and rearranged products. The rearrangement of an unrearranged radical, U•, proceeds to form R• (the clock reaction) with a known rate constant (kr). These radicals react with a trapping agent, AB, to form the unrearranged and rearranged products UA and RA, respectively.[6]

The yield of the two products can be determined by gas chromatography (GC) or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). From the concentration of the trapping agent, the known rate constant of the radical clock, and the ratio of the products, the unknown rate constant can be indirectly established.

If a chemical equilibrium exists between U• and R•, the rearranged products are dominant.[4] Because the unimolecular rearrangement reaction is first order and the bimolecular trapping reaction reaction is second order (both irreversible), the unknown rate constant (kR) can be determined by:[7]

Clock rates

The driving force behind radical clock reactions is their ability to rearrange.[1] Some common radical clocks are radical cyclizations, ring openings, and 1,2-migrations.[4] Two popular rearrangements are the cyclization of 5-hexenyl and the ring-opening of cyclopropylmethyl:[1]

5-hexenyl radical undergoes cyclization to produce a five-membered ring because this entropically and enthalpically more favored than the six-membered ring possibility.[1][4] The rate-constant for this reaction is 2.3×105 s–1 at 298 K.[6]

Cyclopropylmethyl radical undergoes a very rapid ring opening rearrangement that relieves the ring strain and is enthalpically favorable.[1][4] The rate-constant for this reaction is 8.6×107 s–1 at 298 K.[8]

In order to determine absolute rate constants for radical reactions, unimolecular clock reactions need to be calibrated for each group of radicals such as primary alkyls over a range of time.[4] Through the usage of EPR spectroscopy, the absolute rate constants for unimolecular reactions can be measured with a variety of temperatures.[4][5] The Arrhenius equation can then be applied to calculate the rate constant for a specific temperature at which the radical clock reactions are conducted.

When using a radical clock to study a reaction, there is an implicit assumption that the rearrangement rate of the radical clock is the same as when the rate of that rearrangement reaction rate is determined. A theoretical study of the rearrangement reactions of cyclobutylmethyl and of 5-hexenyl in a variety of solvents found that their reaction rates were only very slightly affected by the nature of the solvent.[6]

The rates of radical clocks can be adjusted to increase or decrease by what types of substituents are attached to the radical clock. In the figure below, the rates of the radical clocks are shown with a variety of substituents attached to the clock.[1]

| X | Y | k (s-1) |

|---|---|---|

| Ph | Ph | 5x107 |

| OCH3 | H | 1.4x105 |

| OCH3 | CN | 2.5x108 |

| CN | H | 1.6x108 |

By selecting among the general classes of radical clocks and the specific substituents on them, one can be chosen with a rate-constant suitable for studying reactions having a wide range of rates. Reactions having rates ranging from 10–1 to 1012 M–1 s–1 have been studied using radical clocks.[3]

Examples of use

Radical clocks are used in reduction of alkyl halides with sodium napthalenide, reaction of enones, the Wittig rearrangement, reductive elimination reactions of dialkylmercury compounds, dioxirane dihydroxylations, and electrophilic fluorinations.[4]

References

- ^ a b c d e f Johnson, C.C.; Lippard, S.J.; Liu, K.E.; Newcomb, M. (1993). "Radical Clock Substrate Probes and Kinetic Isotope Effect Studies of the Hydroxylation of Hydrocarbons by Methane Monooxygenase". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 115: 939–947. doi:10.1021/ja00056a018.

- ^ Misik, V.; Riesz, P. Annals of New York Academy of Sciences. 2000, 899, 335–348.

- ^ a b Roschek, B. Jr.; Tallman, K.A.; Rector, C.L.; Gillmore, J.G.; Pratt, D.A.; Punta, C.; Porter, N.A. (2006). "Peroxyl Radical Clocks". J. Org. Chem. 71: 3527–3532. doi:10.1021/jo0601462.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Griller, D.; Ingold, K.U. (1980). "Free-radical clocks". Acc. Chem. Res. 13: 317–323. doi:10.1021/ar50153a004.

- ^ a b Moss, R.A.; Platz, M.; Jones, M. Reactive Intermediate Chemistry. Wiley, John & Sons, Incorporated, 2004. 127–128.

- ^ a b c Fu, Y.; Li, R.-Q.; Liu, L.; Guo, Q.-X. (2004). "Solvent effect is not significant for the speed of a radical clock". Res. Chem. Intermed. 30 (3): 279–286. doi:10.1163/156856704323034012.

- ^ Newcomb, M. (1993). "Competition Methods and Scales for Alkyl Radical Reaction Kinetics". Tetrahedron 49 (6): 1151–1176. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)85808-7.

- ^ Bowry, V.W.; Lusztyk, J.; Ingold, K.U. (1991). "Calibration of a new horologery of fast radical "clocks". Ring-opening rates for ring- and α-alkyl-substituted cyclopropylcarbinyl radicals and for the bicyclo[2.1.0]pent-2-yl radical". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113: 5687–5698. doi:10.1021/ja00015a024.

![k_R = \frac{k_r [UA]}{[AB][RA]}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/c30d9d789baaf0dada177da8c659d480.png)